| Remembrance | ||

|

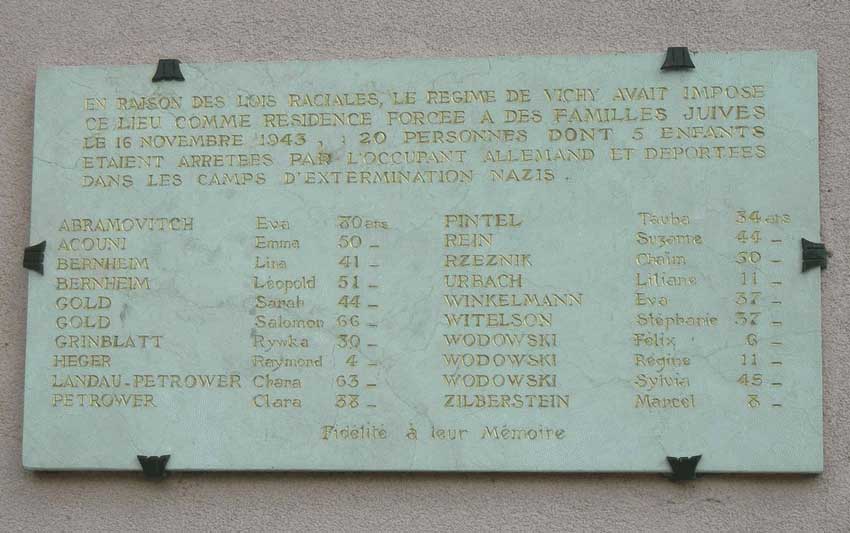

On Sunday, the Anglican church at Coleshill will be unusually close to capacity, if not completely full. And of course the reason is that it is Remembrance Day. There are local and national remembrance ceremonies at which dignitaries take part and where we, as a nation, remember the victims of the last two wars regardless of our personal involvement or not in them. In Coleshill, the Town Band will take part with the usual mix of tunes used for this occasion and of course all the Town Councillors, members of the Servicemen’s associations and generally the great and good of Coleshill will be in attendance to lay poppy wreaths on the war memorial outside the Church. Even Heather and I will be there, with a poppy wreath to lay on behalf of the Twinning Association. Other countries, with other histories remember their war dead at different times and in different ways. But it is something which virtually every country does. Of course, in some countries, major conflicts relate not so much to wars with other states, but to civil wars of various kinds, whether to try to achieve independence or to try to get rid of a dictator, such as in Spain. In these circumstances, how to or whether to celebrate can be quite contentious. France too has its problems, with a collaborationist Vichy government in charge during most of the second world war and so a need to celebrate those who resisted their own government during that period, or who put their lives at risk in order to help during the liberation. But some people living in France were directly affected by Nazi policy. A little boy was playing outside his house in an area of the town of Annecy called ‘Les Marquisats’. He called up to his mother at the window just as officers of the Vichy government were doing a round-up of the Jews in the area. His mother was one of them but, when asked, denied that the little boy was in fact her son. That was the last the boy saw of his family. The parents were held locally for a short period and then sent to their deaths in a German concentration camp. On the front wall of the building in which they were initially confined, near to our apartment in Annecy - now the very pleasant ‘Hotel des Marquisats’ - is a plaque, put up in memory of the deportees, at the instance of the man who was the little boy.  Each year there is a small ceremony to mark the event and, on major anniversaries, there is a gathering of dignitaries including the Prefect of the Haute Savoie, the chief Rabbi and the deputy chief Rabbi for the area. I remarked to the hotel owner, a friend of ours, on one of these occasions that this was a good thing to do. To my surprise, he demurred saying, “Yes, but what about the effect on the present generation of Germans? They are made to feel bad because of their past by such events and the French are encouraged to think badly of them as well”. A fair point. Such ceremonies are arguably a sort of pact between the living and the dead, but we should ask ourselves how much such events give us ‘permission’ to think in bigoted terms about other nations - to encourage a mentality in which it is proper to blame the children for the sins of their fathers - not overtly, perhaps, but by implying that the children conform to the same stereotype as that attributed to their parents during the period of conflict. There is no doubt that such stereotypes are encouraged in time of war between countries. We are asked to think of a whole nation as being our enemy, and as living by different and lower standards than us. In war, propaganda replaces truth. There is no distinction between those of the enemy who may really be against us and those who disagree with what is going on. At the end of any war, however, the hatred and distrust so engendered live on - on both sides - and we become set in our belief that the behaviour attributed to the ‘enemy’ is in fact their national characteristic. An idea the red tops are only too happy to play on to sell newspapers. And so these views are not only those of the generation involved in the conflict but are passed down to the next and subsequent generations. Indeed it is happening now. References, whether overt or implied to the war and ‘the fact’ that we won it are integral to the claims of those wanting to leave the EU. The Muslim community is encouraged by extremists to see Jew and Western infidel alike as their enemy and the enemy of their religion. This is based in part upon Israeli ‘occupation’ of Palestine and underlined in their eyes both by the West’s activities in Iraq and its decadence as judged by their religious values. There is also reference back to the time of the crusades in the middle ages, although a strange omission to mention the crusades by the Arab world which conquered large parts of Southern Europe. We need to do everything we can to discourage such thinking. We should all try to set an example both by refusing to accept such use of national or religious stereotyping and also by making a real effort to bring to an end the re-living of our old conflicts. In that context we ought to continue down the path of making remembrance ceremonies non-specific as regards particular wars and particular enemies. If not, we are part of the same mentality as that which seems to exist in the Middle East, with its memories of wrongs going back not 60 years, but thousands of years - and with the corresponding urge to wreak vengeance. As my cousin pointed out when I discussed this with her, the Jews themselves remember their escape from enslavement to the Egyptians in their Passover ceremony each year - and their exodus from Egypt must have been at least 3,000 years ago! Of course, the young boy who suffered the tragedy of losing his parents will never forget and will, with his friends, continue to meet in front of the plaque to remember those taken from him. Such a very personal loss cannot easily be put to the back of the mind. But national memories of terrible events should be allowed to slide away fairly quickly into the relative calm of the history class, where the circumstances can be properly explained and set in the context of the times. Paul Buckingham 6 November 2019 |

||

|

|