| Freedoms, religion and secularism | ||

| The

current Reith lectures are being given by four

different lecturers. Between them they deal with

freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom

from fear and freedom from want.

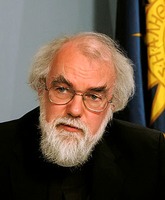

I was particularly interested to listen to the lecture on ‘freedom of worship’ given by the  former Archbishop of

Canterbury, Rowan Williams. His main thesis seemed

to be that, not only should one be free to hold a

religious belief but, through a somewhat extended

definition of worship, be able to act out ones

religious beliefs in daily life. Simply being able

to hold a belief was not enough. One had to be

able to live life in accordance with those

beliefs. former Archbishop of

Canterbury, Rowan Williams. His main thesis seemed

to be that, not only should one be free to hold a

religious belief but, through a somewhat extended

definition of worship, be able to act out ones

religious beliefs in daily life. Simply being able

to hold a belief was not enough. One had to be

able to live life in accordance with those

beliefs. And at first sight, particularly when it comes to an Anglican way of faith in the UK, which is notoriously centre of the road, there is unlikely to be much difficulty. As we have seen, however, in the context of various cases before the courts, there is an attempt by other more extreme wings of Christianity to impose upon the rest of us a concept of life, whether at the earliest moment when, they say, embryos should have full human rights, or at the end when any suggestion of control of the time or manner of ones death should be utterly rejected. Other religions are even more prescriptive. So then, it is clear that the Archbishop’s right to freedom of worship impinges on others' rights. What

though sets a right of freedom of worship on a

pedestal? How is it intrinsically different

to the right for anyone-else - for example me, as

a secularist - to ‘live out my beliefs’, to act

out the values I hold to?

Rowan, if I can get onto first name terms (he’s younger than me, but has more hair), would, I think, suggest that there is a necessary difference: their beliefs come from a transcendent god and so they consider their morality to be a constant in an ever-changing world of opinion, whereas mine, he would say, are just the result of the prevailing thought on any given matter or, in other words, group think. As you might imagine, I don’t find that to be very convincing because, as our very erudite former Archbishop must know, the morality specified by all versions of religion has a habit of changing over time and is different from religion to religion. So then, I don’t find the idea of a separate right to freedom of worship for the religious, as normally defined, to be at all convincing. If there were one, then it would have to be subject to the same limits as those which apply to the actions of secularists. The alternative is for the state to endorse the existence of a transcendent god who sets the rules, which I don’t think we want in the UK, having seen what it does in, say, Iran. Which I think brings us to the question of what we mean by ‘religion’ and ‘religious’. Wikipedia gives us a wordy but fairly uncontroversial definition of ‘Religion’: ‘a social-cultural system of designated behaviours and practices, morals, beliefs, world-views, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, transcendental, and spiritual elements’.I’m not really convinced that this definition of religion goes far enough, but perhaps we should start with what we mean by ‘Religious’. In my view this adjective comes with numerous possible connotations. It can relate not only to religion in the traditional sense, but also to a fixed way of doing things or to convictions held, even in the absence of actual religion, that certain opinions are simply right and others are just wrong. In the past, religion was the arbiter of these things, but things have changed. I think that we can justifiably say that the psychology which creates religion applies equally to encourage the formation and holding of any set of views, social or political or even that our football team is the best. And so in that sense we are all religious. And of course religion’s role in determining how we act was never was as clear-cut as people may have thought, granted the interaction of social opinions, politics and religion. Religion has always been subject to the forces of social evolution, always a work in progress. So then, I would maintain that religion in the sense that we normally understand it is simply a manifestation of our wish as social beings to find a way to live together in relative peace for our mutual benefit, something most of us want to do whether religious or not. Which means that in that sense we are all not only religious, but subscribe to a religion, a secularist, social religion. Of course, living together requires a certain stability of view as to how we should act and so benefits from religion in the normal sense. The rituals, prose, poetry, music, clergy and buildings all give greater permanence to what might otherwise be far more transient standards. And so in this sense, we might be appreciative of the religions which have gone before. Not forgetting that it was always an imperfect means of achieving social stability – religious wars, persecution, clerical ‘misdemeanours’ and so forth. In fact, looking back over the centuries, it was not the secularists who persecuted the religious for expressing their faith, but people of other religions or other branches of the same religion, with the secularists often caught in the cross-fire. It is also the case that in, for example, China, the absence of standard religion has not just created a secular religion, but has seen the installation of a secular god in the person of the Chairman of the Communist Party. It is not simply that people are required to obey the diktats of the party, but are actually required to believe in the Chairman’s opinions on all things. They are examined on it from time to time if they want to climb the greasy pole. In Russia, we have a dictator who has decided that somehow the old boundaries of Imperial Russia must be restored. Although not likely to be found in any religious text, it is a vision supported by the Russian Orthodox church and by its Patriarch who clearly sees the benefit of being on the side of Putin – a Putin antithetical to Christianity, but who has actively supported the Orthodox Church for many years after the fall of the communist party as part of his attempt to remake a stable Russia. A quid pro quo, one might suggest. The form of socialism that we looked at which supported the removal of ‘lesser’ humans by way of selective breeding was also religious in character. It entailed a belief that it was ‘right’ to go down that path in order to improve the gene stock of our species. But if we are, at least in some parts of the world, leaving our religious roots behind us, how else do we achieve social stability? There are fights on-line where there is more outrage than we would ever have thought was possible – outrage about every imaginable thing. John Stuart Mill very presciently warned against the “tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling.”. Indeed, the main excesses in society seem to be on social media - and perhaps in some of the dimmer recesses of university student societies where ever more extreme views are espoused in support of ever smaller, self-identifying disadvantaged intersectional groups in society. I think we can leave the universities to fend for themselves. But the rest of us actually have a choice to make. Should we attach ourselves to social media? If we do, should we all be required to comment under our own names? It would certainly act as a brake on many people’s actions. But then what about people living in repressive regimes? So no. It has to start with each of us. We have to decide whether to be part of the mob or perhaps mere onlookers at these latter-day gladiatorial games. If though as actual participants we made a perhaps initially quixotic effort to moderate how we express ourselves, might that spread? Might we one day realise that our permanent outrage is self-defeating and should be replaced with rather more carefully thought out and nuanced expressions of opinion? 'Think before speaking' - it could be a new religion. Religions always start off small. Paul Buckingham 9 December 2022 |

||

|

|