| Artificial intelligence |

||

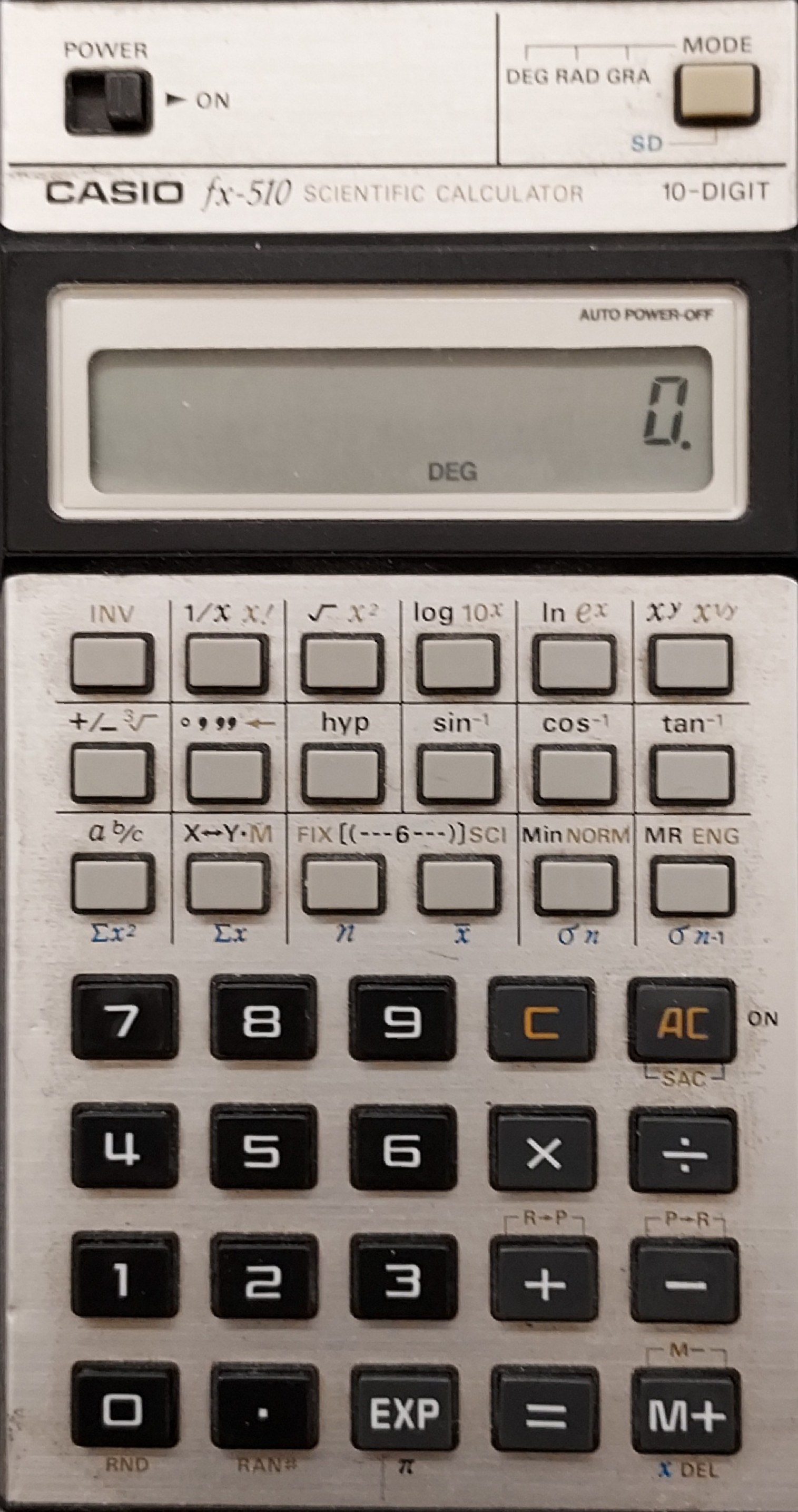

This, of course, comes against a background of progress in computer science which involves vastly more powerful computers with phenomenal amounts of memory. With its parallel processing chips and algorithms, Deep Blue is now able consistently to defeat grand-masters of chess. AlphaGo can beat even the most experienced players of Go and super-computers can outplay the best players of the most difficult American quiz game of all, Jeopardy. It also reflects a vision of computers based on HAL from the space odyssey 2001, a smooth-talking computer with both intelligence and character (even if it wanted to destroy mankind) and the myriad other versions of imagined computer life in dramatic guises which are the cornerstone (with elves and goblins) in the proliferation of on-line games. But at the core of all this there is Alan Turing’s highly influential paper, ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ (1950). In it, Turing argued that if a hidden machine’s ‘answers’ to questions persuaded a human observer that it was a human being, then it must be regarded as genuinely thinking. If it expressed its ‘thoughts’, that is if it responded to questions just like a human, it must be the equivalent of a human. But this is not necessarily true. It is a conceptual muddle. To infer that our simple inability to distinguish between a real human and a computer, based on what it ‘says’ means that there is in fact no difference, is not a conclusion we can logically draw and it would certainly be huge step to take based on such a small amount of evidence. If I cannot tell whether someone is lying, it does not mean that I have to assume that he is telling the truth - I can instead say that I simply don't know and look for further evidence to support one or other conclusion. Even then, I can caveat my opinion by saying, for instance, that it is more likely than not that he is lying, so leaving the question open. After all, our ability to make judgements about others is often quite poor. And, again, why should the chatbot’s ability to say that it fears death mean, even prima facie, that it has achieved sentience, that it can actually feel afraid of future events? Is it not more likely that in its search of massive databases, it has found that asking human beings what they are afraid of will often produce the answer: ‘death’? The term ‘Artificial intelligence’ is in any event an overblown and ambiguous way of expressing what we think we can achieve with computers.  I have a Casio fx 510 scientific

calculator which dates from about 1980. It still

works – I’ve just replaced the batteries – and it’s

a lot more reliable than I am in carrying out

calculations. It is in good condition and something

of a rarity (I’ve seen one at £80 on eBay). I have a Casio fx 510 scientific

calculator which dates from about 1980. It still

works – I’ve just replaced the batteries – and it’s

a lot more reliable than I am in carrying out

calculations. It is in good condition and something

of a rarity (I’ve seen one at £80 on eBay). But although I need to understand what I’m doing, I don’t believe that the calculator has any actual concept of calculation. I enter data, press a few buttons and an answer appears. It doesn’t need to ‘understand’ what it is doing any more than did its predecessors, the slide rule or the abacus. It is a tool, hard-wired to carry out certain tasks, just as a light switch when clicked will turn a light on or off – assuming the bulb is working! But Artificial Intelligence has acquired a reputation for being in a different category. It has code, its ‘algorithm’, which enables it to search for patterns in vast amounts of data in order to be able to solve problems that we would have difficulty in answering. Such algorithms can even modify themselves so that they can try out new, more effective, ways of doing things and so better achieve the desired goal. Just like us when we learn. Because, although not as efficiently, we too recognise patterns in data and adjust our approach to problems accordingly. That’s how we progress in our lives. As babies we don’t come with a built-in encyclopaedia. Instead, we come with built-in inquisitiveness, a desire to know how the world works, pleasure receptors which encourage us to take actions and pain receptors which tell us to avoid other things. We have other senses, such as hearing and vision, which all enable us to interact with the world around us. But unlike Google’s chatbot we also have a concept of self, our sentience. When the chatbot replies to our questions it does no more than look for clues in the question which will tell it what part of the immense amount of data to which it has access can be turned into an answer which will satisfy me. That it is not assessing the data independently or intelligently is evidenced by the numerous examples of the prejudiced replies it produces from the prejudiced data it is searching to give those answers. It does not seem to filter the data for rationality or prejudice or ask for further information or surveys of opinion to be carried out before it replies. In fact it is obvious that it lacks judgement altogether in the normal human sense. Does it in any real way actually ‘understand’ either the question or the answer and their ramifications? Of course not. Why would it need to? Surely that would be a waste of processing power even were it possible. When Deep Blue plays chess does it have any concept of the human emotions which drive us to compete? Does it understand that its programming is in fact a part of a drive by us to see how best to write code which will produce better results each time? Has it twigged that its mastery of chess is only a side-effect needed to draw the public’s attention to it and so get more funding for the AI project? No? Well that's what we humans do. And that ability to strategise, to see the big picture, our general intelligence, distinguishes us from the machines - at the moment. Currently we are not really trying to make machines which can think like us, just machines which can do selected tasks better than we can - without their knowing what they are doing or why they are doing it. Will the day come when we can indeed produce intelligent machines with an awareness of the world around them? There is of course the slight difficulty that we do not know how we ourselves have sentience, although some of a religious persuasion would say that it is an add-on given to homo-sapiens by our creator. If though we simply believe in a physical world of causes and effects, then there is no reason to think that creating self-aware intelligence is impossible in principle. After all, we exist, as do other animals. And the more we study the animal world, the more we seem to see signs of sentience which, along with some degree of intelligence, enables them to live their often complex but relatively limited lives. Why though would we want to take that next step – the creation of artificial, sentient intelligence? Leaving aside all the dystopian futures portrayed by Sci-fi films, there would seem to be little point in creating ‘I Robot’. Why would we want to create a sentient being, capable of surviving on its own and so with the emotions necessary to motivate it and the intelligence to understand what’s going on? What’s in it for us? Even the war lobby would balk at developing sentient war machines. They might turn on their creators and become pacifists. Surely we should continue to develop unthinking machines which can be absolute experts in narrow fields where they can help us human beings to live better, healthier lives. And this without our having to decide what emotions they should have, provide them with radio phone-in shows so that they can express their feelings - or ever have to engage with them in small talk. Paul Buckingham I November 2022 And see: http://paulbuckingham.com/Artificial Intelligence.html |

||

|

|